The Legend of Jinky, the Moville Master of Disguise

Did Celtic starlet Jimmy Johnstone play incognito in Irish tournament to raise church funds?

The first Covid lockdown had not long begun when I met a neighbour in the field by my house. We were, as per the government guidance, standing the requisite distance apart as I was engaged in one of the strangest conversations – at least from a journalistic perspective – I’d ever had.

Lockdown had its consolations for us writers. Interviewees, evidently bored out of their minds, would answer the phone and still be chatting hours later – a rare but welcome phenomenon for journalists attempting to gather as many specifics as possible for whichever story they happened to be working on. That spring day, my neighbour told me in some detail a tale so extraordinary that I initially felt certain it could only be an urban myth. I spent a week researching it for a piece in The Herald, speaking to witnesses and those who had had the story passed down to them.

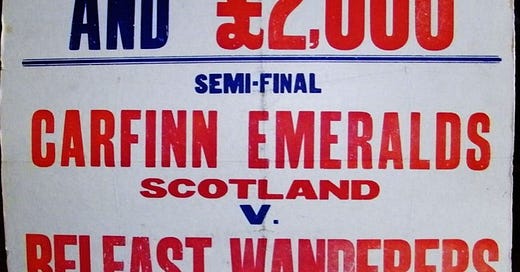

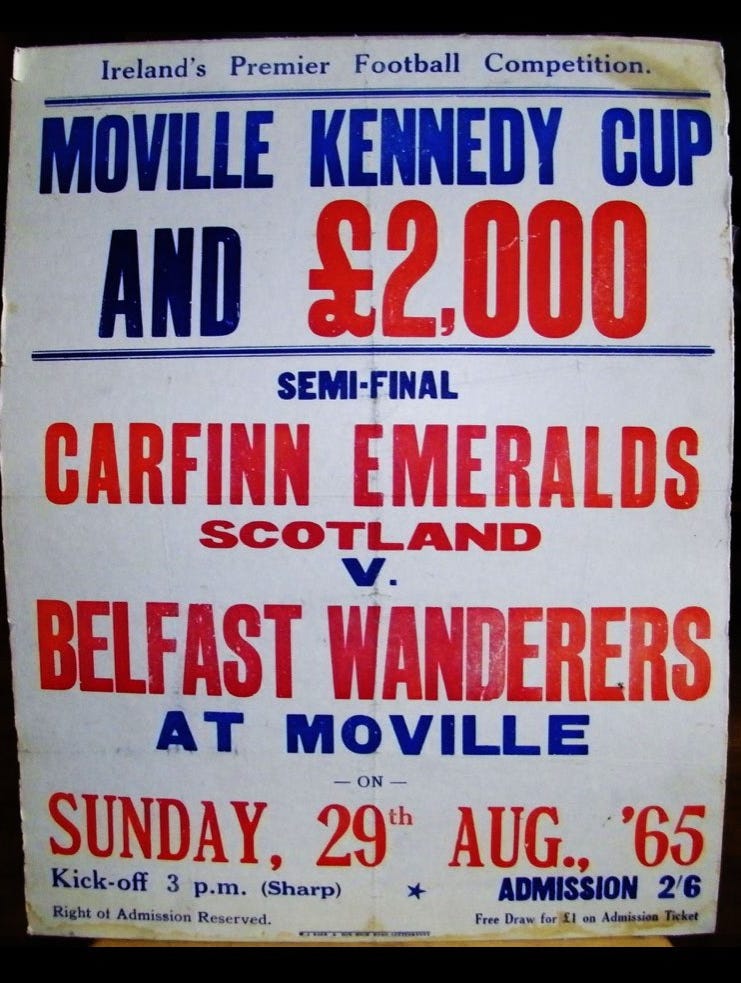

The County Donegal town of Moville used to hold a summer football tournament called the Kennedy Cup with a £2,000 prize fund. Teams would travel from across Ireland and further afield to compete in it, usually loaded with professional and semi-professional players. One such team, the Carfin Emeralds, won the tournament in 1964 and legend has it that as many as nine Celtic first-team players were in their ranks. The suggestion was not as ludicrous as it sounds today: Paddy Crerand, the Scotland and Manchester United midfielder who won the European Cup in 1968, played in the Kennedy Cup in the early ’60s, as did Johnny Crossan, the Northern Ireland and Manchester City midfielder. In the summer of 1961, the Celtic players Mike Jackson and Billy McNeill competed in a tournament in Spain without the permission of their club or the Scottish Football Association. They were photographed walking down the steps of a plane after their flight back to Glasgow, landing themselves in hot water with both Celtic and the governing body, and were each later fined £50.

The story of the 1962 Carfin Emeralds entrants was like an episode of Father Ted. An Irish priest – a certain Father Jack Gillen, formerly of Moville – needed funds to continue the building work on St Teresa’s Church in his parish of Newarthill in North Lanarkshire and alighted on the idea of putting together a football team to play in the lucrative summer tournament in his hometown. If they could pull off that feat, the prizemoney would go a long way to completing the new chapel.

Professionals were rumoured to be in the ’62 Emeralds team, including ex-Scotland internationals. It would certainly explain why, when the players took to the Bay Field football pitch in Moville for matches, most of them were wearing disguises – from masks and boot polish to glasses, wigs and false beards. The name Jimmy Johnstone cropped up more than once. The Jimmy Johnstone. Jinky, as he was affectionately known, who is immortalised in statue form outside Celtic Park alongside Brother Walfrid, Jock Stein and Billy McNeill. Was Celtic’s greatest-ever player really putting his body on the line for a ragtag team in Ireland just a few years before he won the European Cup against Inter Milan in Lisbon?

Most of this part of the story is documented in my Herald piece, Irish newspapers of the day, and a few articles on websites and in Celtic publications by people who, like me, had become captivated. Less well-known is the Scottish version of events, however. Enter Tommy McGinn, a bricklayer from Lanarkshire and a friend of Father Gillen’s who helped run Irish nights in Hamilton Town Hall and who was a pal of the Irish comedian Frank Carson. Tommy was the manager of the Carfin Emeralds. He died a few years ago but a telephone call to his brother Charlie revealed that Tommy and Father Gillen would tour Lanarkshire towns such as Croy, Viewpark and Uddingston, taking in football matches with a view to recruiting players. They were a prolific partnership, and Father Gillen would give the hard sell to entice the players. This included details about their cut of the Kennedy Cup jackpot and which bookmakers would be willing to take a bet on Carfin winning the trophy. Father Gillen’s family owned a hotel in Moville and so food, drink and accommodation would be provided; the players would only have to pay for their boat ticket. However, the players’ biggest concern was that they could play without being exposed.

“Father Gillen had to take a chance, he couldn’t insure them in any way,” said Charlie. “People said it was Father Gillen’s team but he took a back seat once it was up and running, he didn’t go over for the matches. My brother was the main man for recruiting the players. Father Gillen was the one reassuring them that it would be all right because it would be to raise funds for a church in Newarthill.

“A lot of the players said: ‘I’ll play, but I don’t want to get into any trouble with my team.” One of the parishioners, Christy McIvor, was in amateur dramatics, so he was the one who set them up with the beards and disguises. There were a lot of people watching and there were a lot of cameramen at the games, and people looking for information all over the place. The lads couldn’t afford to be found out.

“My brother would convince the players that they would be masked up and they would be all right with their clubs. Christy went over to the games in Moville to see that things were all right, to make sure they were all made up.”

Unfortunately, because it was patently obvious that most of the players were wearing disguises, onlookers and the local press endeavoured to establish their identities. It certainly made for great copy. The Aberdeen Evening Express reported on July 19, 1962: “The ‘mystery’ footballers from Lanarkshire, the Carfin Emeralds, flew out to-day from Renfrew Airport, Glasgow, for another series of games in northern Ireland. One of their officials explained before boarding the plane for Belfast: ‘There is nothing [to] hide about us. We have no professionals and none of our team is signed for any club. Apart from this week-end when they are on holiday, some of the lads have taken a few days off work to play in Ireland. They would get into trouble if their bosses found out.’”

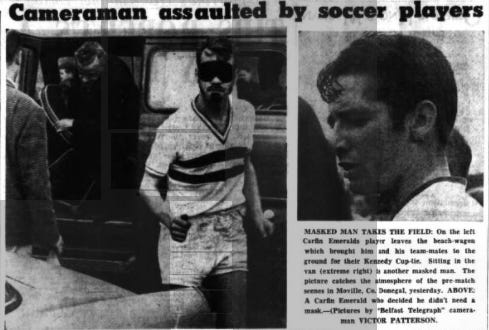

Ten days later, a report appeared in The Belfast Telegraph about how angry Carfin Emeralds players had confronted their photographer when he had snapped them as they exited the tournament at the quarter-final stage:

A Carfin player who was being photographed punched the cameraman, another kicked him, and the contents of a mineral water bottle were thrown over him. The Pressman was able to get away only when a couple of other members of the Carfin side came to his assistance. This was an ugly scene which destroyed completely the gimmicky carnival atmosphere Carfin may have tried to create by appearing in masks, dark glasses and false beards.

Officials of the Scottish team repeated that the players were amateurs who, on the occasion of their first trip to Moville, had taken a week-end off work and didn't want their employers to know. Hence the refusal to give names. But this hostility to the Pressman seemed to indicate even stronger reasons for avoidance of publicity.

Only one of the Carfin players was undisguised; centre-half Frank Brennan, the ex-Scottish international. But as far as the Moville competition is concerned the Carfin Emeralds’ bubble is burst. In a tough, no-quarter given game, Albert Celtic, Belfast beat them 3-2.

Some of the Belfast players played with false beards and moustaches. But one of their officials supplied a team list to the Press and said — “They have only put on the disguise for laughs. The team is made up of amateur players who have nothing to hide. We have been playing in this competition for several years now.”

Of course, the reason for the disguises was not high-jinx but indeed to prevent the players from getting into trouble with their clubs. So was Jinky one of the 1962 mystery men? Back then, the winger was aged just 17 and plying his trade in the Celtic reserve team, and not the instantly familiar figure he would become. Therefore any attempt at disguise would only have been to prevent photographic evidence from getting back to Scotland and people who might have recognised him.

In an effort to shed more light on the puzzle, I spoke to a man who was making a film about the Kennedy Cup. Tom O’Flaherty had worked as an editor on a number of sports and music films including documentaries about Dennis Rodman, the Ireland rugby team, David Haye, Van Morrison, U2 and The Chieftains. Tom had in his possession Super8 camera footage of a man roughly fitting the description of Jinky. I say “roughly” because this individual looked stockier and taller than Johnstone. The players is wearing a mask to protect his identity and has a shock of ginger hair, but some have suggested that this was dyed. Tom was certain this was Jinky, but the footage is from the 1964 tournament and there are real doubts that Johnstone went to Moville that year. He certainly visited in the 1970s, as Tom testified: “I saw the presentation of the Eamon Gillen Memorial Trophy (which replaced the Kennedy Cup), and Billy McNeill, Bobby Lennox and Jinky Johnstone were over in the Bay Field presenting that trophy. I know that for a fact.”

But did Johnstone ever actually play for Carfin Emeralds? There was a rumour that the Derry City manager at the time pursued him all over Moville – from pub to pub – in an effort to sign him.

“No one ever got to the bottom of who played or didn’t play, but it was a great buzz at the time with these guys running out with their faces covered in boot polish. It was a bit of craic,” former City goalkeeper Eddie Mahon told me.

Eddie himself played in the Kennedy Cup, but he doubted whether the Johnstone story had any truth to it, even if he enjoyed keeping the myth alive. “People still talk about it and it loses nothing in the telling,” he added. “I personally would be sceptical if there were any big names. Jimmy Johnstone is the one that always crops up. That would have been maybe 1962. Maybe he was a kid coming through. It’s a bit like the Loch Ness monster – we’ll let the legend continue.”

If there was one man who could clear up the mystery, it was Charlie McGinn.

“A lot of people around Carfin and Newarthill said they knew this or knew that about it – but they didn’t,” he said. “Over the years, this one and that one were supposed to have played but it was mostly a secret because all of the lads were playing football and they didn’t want to get into trouble. Half the team would have been senior players and the rest was made up of good junior players ready to step into the senior ranks.

“Wee Jinky Johnstone? Aye, he played. It would have been the early ’60s. Wee Johnstone was just coming through with the Celtic reserves. That area – Viewpark and Uddingston – there was a lot of players from down there, junior players ready to get signed up for senior teams.”

So there you have it. A Kennedy Cup medal would evade Jinky in 1962 after that defeat by Albert Celtic. He would have to settle for a European Cup winner’s medal instead.