In My Sporting Hero, a new podcast series from Nutmeg, footballers talk about the athletes who inspire them. Sometimes those sportsmen and women are also footballers. Sometimes not. You can listen to the audio on this post, on the podcast app of your choice (just search for ‘My Sporting Hero’) or enjoy the written version below.

Our next guest is John Colquhoun.

John is best known for his two spells at Hearts. He was part of the fine side that was pipped to the 1985-86 league title, and to this day is remembered at Tynecastle as a club great. The pacy winger scored 101 goals in 424 competitive matches for the Jambos, and since hanging up his boots has been a university rector, a football agent, a sports columnist and a golf product entrepreneur.

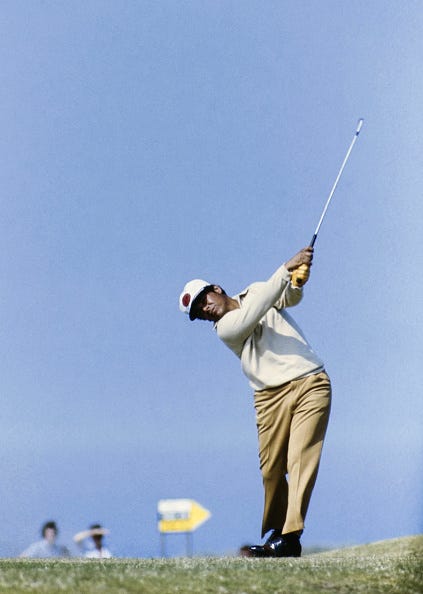

John’s sporting hero is Lee Trevino, golf’s rags-to-riches maverick who defied his lack of physical stature to win six major titles.

For many years, I thought that Lee Trevino was Mexican until I found out that he was actually born in Texas. He was my first sporting hero, and because we didn’t have the overfamiliarity that we have with today’s superstars, he retained a certain level of glamour for me. He would appear once a year on our TV screens during the Open, and the best way I can describe him is swashbuckling. He would swagger down the fairway up against the likes of Tony Jacklin – great players, world-class athletes but men that looked to me just functional, whereas you had this wee guy with a swing like nobody else. He would do amazing things around the green.

I’ve got a little golf business that is built on the swing of Ben Hogan. Hogan had a book called Five Lessons: The Modern Fundamentals of Golf, which is an amazing book and easy to follow, which is good for somebody like me who doesn’t really understand the intricacies and mechanics of a golf swing. The new version has a foreword by Lee Trevino, and these are my two great golfing heroes, although Lee was my original hero. Lee calls himself an accidental golfer, because the only reason he became a golfer was due to where he was brought up – in a shack in Texas with no electricity or running water which happened to be near one of the big country clubs in Dallas. He realised he could make a few bucks by caddying and helping out there, and eventually he went into the services and then returned and became this great golfer. But a lot of his greatness was purely natural, because he wasn’t formally educated in the game.

Nowadays, you would probably have an overcoached athlete management system – in every sport. My main sport is obviously football, but in every sport everyone is now taught not to take risks. In football, it’s all about, “keep the ball, keep the ball,” which is obviously what Pep Guardiola’s sides do, but Pep keeps the ball to get an overload, find the space and then get the ball forward as quickly as you can, whereas when I watch under-12 games and people say “keep the ball,” I just walk away because it dispirits me; I never hear anybody saying, “take a risk.” And it’s the same with golf swings. You see some amazing golf swings, functional and powerful, but then you look at the guys from the old days, and you realise you couldn’t have taught Lee Trevino his swing. Okay, maybe it became a bit more conventional over time, but he looked like an entirely different type of golfer.

Maybe it’s a bit to do with my little man syndrome; Lee wasn’t a giant and perhaps psychoanalysts could explain why I was so drawn to him, and also why I loved Jimmy Johnstone and why a lot of my heroes were vertically challenged. I’d take Maradona over Pele, Messi over Ronaldo. I always go for the wee guy. Maybe that’s because I’m a wee guy and I see myself in them and I understand the challenges they faced. Think of the challenges Rory McIlroy faces: a man of his height, hitting the ball as far as he does. It’s remarkable, and nobody ever comments on that. Trevino looked like a streetfighter. He was always laughing and joking, but all of a sudden, if something went wrong, you wouldn’t mess with him. Seve was the same, in that they weren’t traditional country club graduates, guys with the wealth to fly around and go to all the best tournaments. I feel that they made it in spite of the system, rather than because of the system. Seve worked on his game on the beach, learning the game through instinct and feel.

Going back to Ben Hogan’s book, Lee finishes his foreword with a brilliant quote about the lessons of Hogan: “Take it all in, or be selective. Master the basics, but always leave room for self-discovery, just as the man who wrote it did. There are different ways to play golf well, but nobody has ever hit shots more correctly or with more control than Ben Hogan.” The most important bit of that quote is “self-discovery,” and you feel as though with Trevino, a lot of it was off-the-cuff. And the off-the-cuff guys, I believe, are the ones who bring the big moments.

We are terrified of people being themselves

I understand why world-class athletes now are very wary, because everybody’s waiting for a gotcha moment, especially with social media. You look at when the PG Tour mic people up, and I think they mic-ed Rory up in one of the tournaments, and a lot of people criticised him heavily saying, you’re there to win a tournament, you must be focused. But I’m not sure that’s true, I think we are just terrified of people being themselves. Yet I think many people are now looking for more authenticity in our heroes.

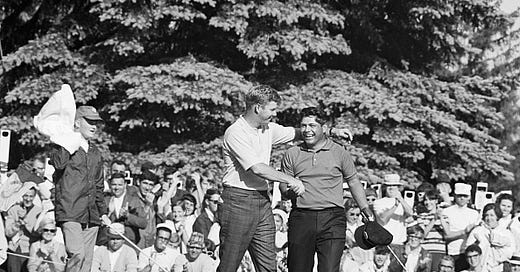

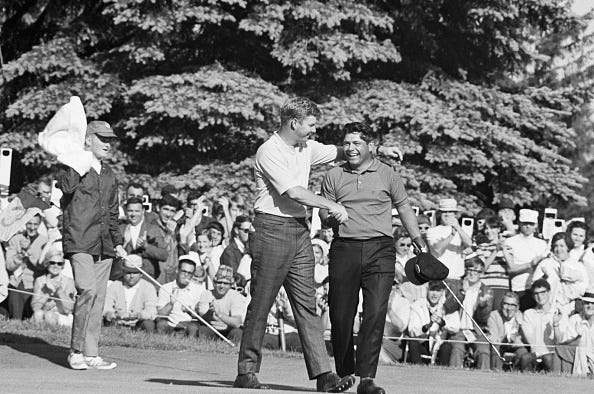

I was at the PGA show in Florida last year and Lee Trevino was making an appearance and I was hoping to even just catch a glimpse of him, but it didn’t happen. I would love to meet him, and if I had my ideal dinner party, he would be the first name on the guest list. You wouldn’t even need anybody else because he would just talk all night about all the great stories and the great adventures that he’d had around the world. To beat Jack Nicklaus, to face him down in a major must have taken immense strength of character. When you consider the poverty Lee was brought up in and what he had to do to survive, you realise why he had that fighting spirit, but you’ve still got to drag it up when the margins are fine and the pressure is on. So it was incredible that he was able to do it against Nicklaus and all the great players of that time. Good golfers can all conjure up shots, but a lot of them will only be able to do it on the practice rounds. Doing it on the 17th hole, when your forearms are tightening, and the cameras are on you, and your opponent is staring you down, and you know people are desperate for their guy to win it – to still be able to free your mind up and stop your body from tightening so that you can maintain that creativity and keep running and spinning those balls in, it’s just amazing.

When I was young, we didn’t have the wall-to-wall sports coverage that we have now. If we were lucky, there would be the Olympics or the World Cup on TV, but our summer would largely be defined by participating in sport. The first two weeks in July were Wimbledon, and we would actually make a court somewhere. For the next two weeks, it was golf. You’d always pretend to be one of the stars, even though we’d only have about three clubs. There were no golf or tennis lessons for us. Then we’d go back to school, and we’d be back into football, cross-country running, rugby and swimming – nothing else. It was only in the summer that we watched any golf. I can’t remember, up to my late teens, even knowing that there was a golf tournament called the US Masters. I didn’t watch it until the European invasion arrived, with the likes of Seve Ballesteros, Sandy Lyle, Nick Faldo and Ian Woosnam winning it. Sandy was Jack Nicklaus’ Sunday playing partner when Jack won it in 1986. Sandy told me about that when I was lucky enough to play with him in a ProAm at Archerfield. He was great company. I was also lucky enough to play with Ian Woosnam – another wee guy who could hammer the ball and who was also great company. He was a grafter who had to work harder than the rest of them, but he could hit it for miles.

That grafting is the whole point. Years ago, when I wrote for the Scotland on Sunday, I did an article entitled Barroom Peles. A group of professional footballers from Stirling would meet up in a pub after playing on a Saturday for a debrief. Guys like Robert Dawson who played with St Mirren, John Philliben of Motherwell, Brian Grant of Aberdeen. There would be failed footballers there too, drinking, and occasionally one would claim that he was a better player than any of us. And I would reply, “What were you doing this afternoon? We were playing in front of eight, ten, twenty-thousand people.” These guys might have had better ability than me, but football is about more than just ability, it’s about discipline, too. And men of Trevino’s size, of Woosnam’s size, of Rory’s size, of Messi’s size – they’ve got to be so disciplined. And I admire all of them because they achieved that.

Share this post